The celestial body most similar to Earth in the solar system was visited by the Huygens probe after a journey of more than 7 years. What did it find when it landed there?

|

| Artist’s impression of methane rich lakes on the Farthest World where a human made spacecraft has landed. (Jurik Peter/Shutterstock) |

Ever since man ventured into space, he has sent the technology to many corners of the solar system. Before the end of the 20th century, our probes had already touched the surfaces of Mars and Venus, but it would not be until 2005 that a spacecraft would land on the most distant world to date: Titan, Saturn’s largest moon.

The protagonist of the feat was the Huygens probe, designed by the European Space Agency (ESA) and launched into space on October 15, 1997, as part of the Cassini-Huygens mission (orbiter and landing probe, respectively).

|

| According to astronomers, Titan has similar conditions to Earth in its first years of life. Photo: ESA / NASA / JPL / University of Arizona |

The objective of this joint project with NASA and the Italian Space Agency (ASA) was to get to know Saturn in depth: its rings, climates, geology, and dozens of moons. But the Huygens instrument pointed to the most gigantic Saturnian satellite of all.

Why is this distant body in the outer solar system still so interesting today?

Titan is a special world for astronomers not only because it is the second-largest moon in the solar system after Ganymede, of Jupiter; but because of its very similar conditions to the primitive Earth.

Similar to the blue planet, Titan has a 600-kilometer-thick atmosphere that is made up of nitrogen (95%) and methane (5%). It is also the only other place in the solar system where a rain cycle similar to Earth’s has also been seen, with the exception that it is based on methane instead of water.

Continuous precipitation—which varies depending on the seasons on the planet, also tilted like Earth—makes Titan’s surface changeable. Mainly at its south pole, there are liquid reserves (lakes and seas) and hard ice rocks due to the extreme cold of -180 ºC.

Astronomers believe that in 6 billion years when the Sun becomes a red giant star and its size brings it closer to the outer solar system, conditions on Titan may be favorable for stable oceans.

|

| Images taken by Cassini show the changing surface of Titan. Photo: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona |

All these characteristics make Titan one of the best candidates to have harbored (or harbor) extraterrestrial microbial life that depends on methane instead of water.

|

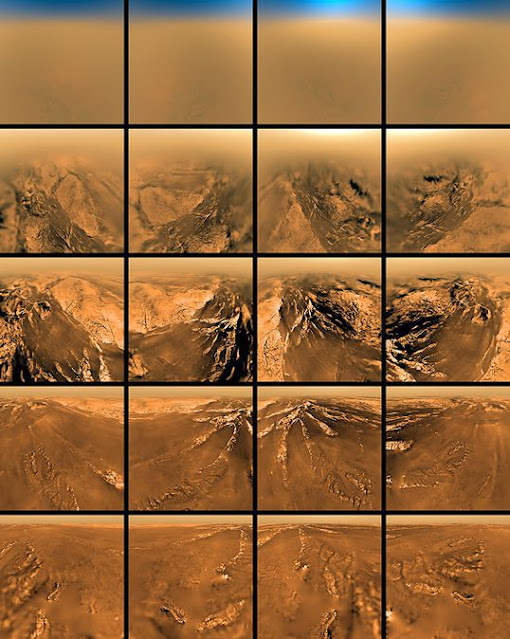

| Images of the surface of Titan taken by the Huygens probe. Photo: ESA/NASA/JPL/University of Arizona |

Seven years after the launch of the Cassini-Huygens mission, the Cassini module was inserted into the orbit of Saturn. Then, in December 2004, it ejected the Huygens probe, its traveling companion who had been ‘asleep’ for all those years, towards Titan.

The violent entry into Titan’s atmosphere in January 2005 took almost two and a half hours. Once on the surface, its useful life was very short but valuable: for one hour and ten minutes, it worked automatically and captured 350 photographs of the terrain before losing communication with Cassini, which moved away from the landing point and followed its orbit.

The computer and postal data of the impressive descent to Titan were recorded for history and, years later, were recreated in an ESA video.

The images show rocks similar to boulders, so it is believed that there was a fluid that ran through there and eroded them.

But the interest in this giant satellite has not ended.

Dragonfly, the dragonfly that will fly over Titan

Continuing the legacy of Cassini-Huygens, in 2026 NASA will send the Dragonfly mission to Titan to study the satellite’s atmosphere, its prebiotic chemical processes, and its subsurface ocean reserves.

This flying instrument – similar to the Ingenuity on Mars – will land in 2034 in Shangri-La, a region with dunes similar to those of Namibia in southern Africa.

From then on, Dragonfly will make long jumps of up to 8 kilometers in different locations and, in each one of them, will stay one Titan day (16 Earth days). Its ultimate goal will be Selk Crater, a region where evidence of ancient liquid water exists.

“Visiting this mysterious marine world could revolutionize what we know about life in the universe. This state-of-the-art mission would have been unthinkable even a few years ago, but now we are ready,” former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said in a statement.

Dragonfly is part of NASA’s ambitious News Frontier program, which includes other missions such as News Horizon to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, Juno to Jupiter, and OSIRIS-REX to asteroid Bennu.

Reference(s): NASA